Welcome back for Part 4 of my series on why knees break-down over a lifetime! In Parts 1 and 2, we explored how mechanical loading and inflammation interact to drive knee joint degeneration and pain. In Part 3, we covered how muscle function plays a key role in regulating mechanical loading and inflammation as well as maintaining working knees to support an active and fulfilling life-style. Specifically, we talked about what muscles do and how they are able to do it through a combination of strength, power, endurance, activation, and mobility. This fourth, and final, installation in the series will piggy-back off what we learned about muscle function to more specifically explore how our actual movement patterns can impact life-long knee health.

How do we define movement quality?

The concept of movement quality can be somewhat vague. How can we determine that someone is moving “well” or moving “poorly”. This is going to depend on the specific anatomy, movement goals, and history of the individual person. While we can’t give a blanket statement as to whether any one movement or movement pattern is entirely good or entirely bad, scientists and clinicians have developed concrete ways of measuring and quantifying the quality of movement to give us a baseline from which to start this conversation.

Space and time: The first, and arguably easiest, method we can use to quantify movement quality is by describing movement in terms of how the body moves through space and time. To quantify how a body moves through space, we may talk about qualities of movement like step length (how far the leg moves with each step), step width (how far apart the feet are with each step), and step height (how high the foot is lifted up with each step). To quantify how a body moves through time, we may talk about qualities like walking speed (how fast a person moves as they are walking) and step cadence (how many steps a person takes over a defined period of time). You can begin to imagine how these measures could be useful to determine knee degeneration. For instance, if a person is walking slower and is taking shorter steps on one of their legs, you may conclude that this person has an injury and is limping on the injured limb. These measures are useful as they can be captured by simply watching how a person moves or by using every day devices like a smartwatch or simple wearable sensors.

Body positions: We can get slightly more complex by quantifying the specific positions of individual joints during movement. This is usually measured in terms of angles, or degrees, of joint bending. For example, we can see someone walking with a stiffened knee and quantify the limited degrees of knee bend, or we can see an older individual hunched over a walker and quantify the excessive degrees of forward bend at the hips. By quantifying specific joint positions at different times during movement, we can get a better idea of what is happening, or has happened, in the body. Building off the example above of the individual who was limping, we may see very limited knee bending whenever that person steps on their injured limb and determine that the injury has something to do with the knee joint. Trained professionals, like physical therapists, are experts at watching movement and identifying subtle alterations in joint positions, but it requires more advanced technologies, like wearable sensors and motion capture, to actually quantify these alterations in joint positions.

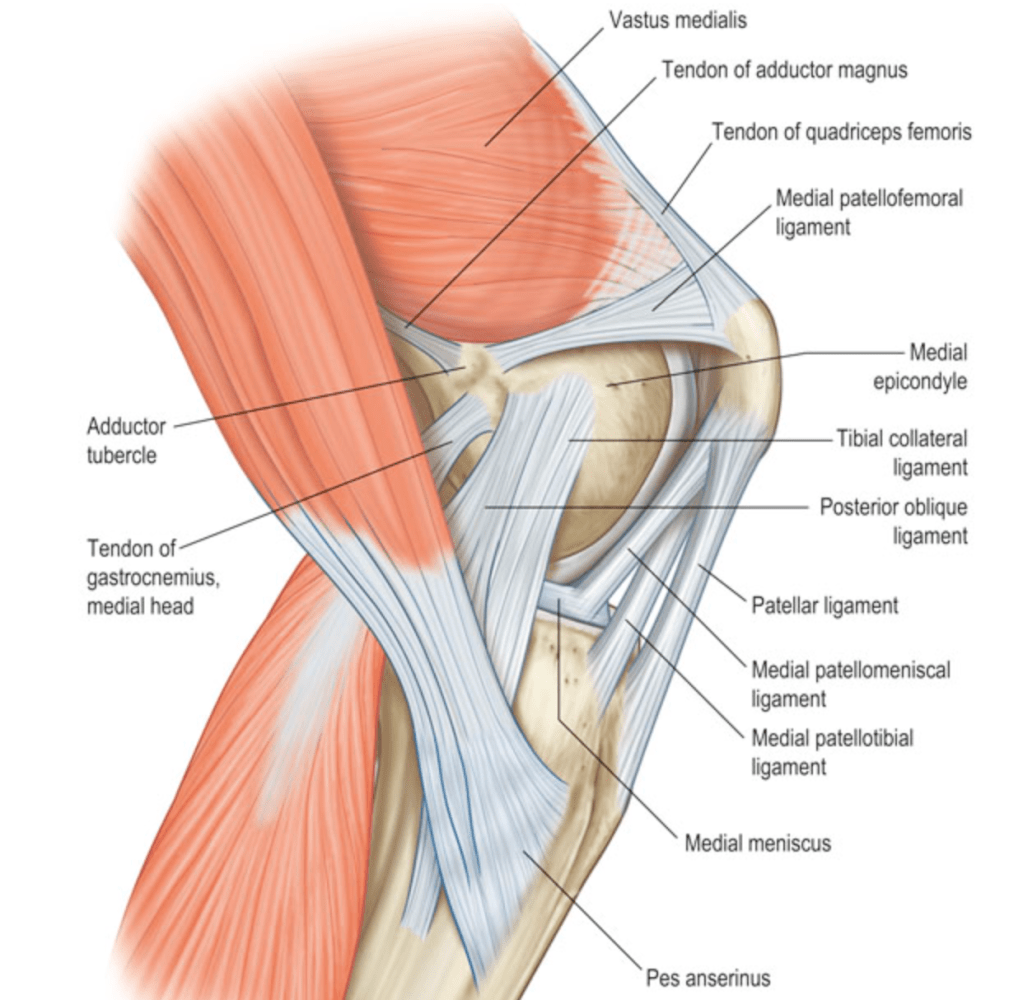

Forces: To get a near complete picture of movement quality, we need to determine the forces at play with each movement. The forces acting on the body can come from outside the body, such as impact from the ground or gravity, or from inside the body, such as muscle contractions or tension in ligaments. Regardless of where they come from, the forces acting on the body directly inform how the body creates and responds to movement, and they can give great insight into a person’s pathology (state of dysfunction) and their path to recovery. Going back again to our limping example, we could measure the forces on that limb and determine that the person is walking with reduced impact on the ground (less weight-bearing) and is generating much lesser forces from the quadriceps. From this, we may suspect that this individual has some degree of quadriceps impairment. Further, we may suspect that this person is at greater risk for future cartilage degeneration as less of the ground impact is being mitigated, or absorbed, through the quadriceps muscle. Unfortunately, quantifying the forces through the body is difficult to do and requires advanced technology to do accurately. Experienced clinicians, like physical therapists, and some clinically accessible technologies can often make accurate guesses as to what are the general forces acting through the body, but this is an important area of ongoing research.

F.I.T.T.: With these increasingly complex methods of quantifying movement quality, I want to bring it back to an accessible method of generally quantifying movement defined by the acronym F.I.T.T. This acronym stands for:

- Frequency: How often you are moving

- Intensity: How strenuously you are moving. This is a good indicator of the forces through your body

- Time: The duration of each bout of movement

- Type: In what way you are moving you body. This can largely determine how your body is moving through space and time

Using F.I.T.T., you can start to get in idea of how you are moving on a daily basis without specialized equipment or help from a professional

What is the impact of movement quality?

Now that we have a basic understanding of how movement quality can be defined, let’s talk about how changes in these parameters can impact the bones, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and cartilage in your knee joint.

Magnitude of load: By magnitude of load, I mean the absolute amount of load, or force, that is being placed on the knee. Remember from Part 1 that too little or too much loading on any tissue in your knee, but especially the cartilage, can contribute to tissue degeneration. Thus, the way that you move can increase or decrease the loading through your knee to promote either positive or negative changes for long-term health. Imagine that you adopt a movement pattern which places significantly more load through your left knee compared to your right. In this instance, your left knee may be at risk for degeneration due to excessive loading, while your right knee may be at risk for degeneration due to insufficient loading and atrophy.

Location of load: Your movement patterns may also change the location of the load placed through the knee. This could mean shifting the loads within a certain position on a tissue to a different position on the same tissue. For example, walking with a stiff knee may shift the loads through the articular cartilage from an area which is thick, strong, and capable of absorbing load to an area of the articular cartilage which is thinner and not as adept at handling loading. This could also mean shifting the loads from one tissue to a completely different tissue. For example, that same stiffened knee walking pattern may shift the load with every step from the resilient quadriceps muscle to the much less resilient articular cartilage of the knee. Lastly, your movement pattern may shift the loads experienced during a movement from one joint to another. By landing from a jump without sufficient hip bend, the impact of landing is no longer shared through the strong muscles of the hip and the knee, rather, all the impact shifts to be placed through the knee joint.

Frequency of load: Whether it’s by changing how often you move, the type of movements you are performing, or the positions you are putting your body in during those movements, your movement patterns can alter how often a certain tissue gets loaded. For example, if you choose to pick up running as a hobby, but you adopt a running pattern that stresses your patellar tendon rather than your resilient hip or ankle muscles, then you are greatly increasing the repetitions of potentially harmful loading on your patellar tendon with could create pain and breakdown on the front of your knee.

Efficiency, efficacy, and comfort of movement: Remember, getting you from point A to point B during weight-bearing movements is the ultimate function of the knee joint. Sometimes, we can adopt movement patterns that unnecessarily increase the amount of energy needed to complete a movement, decrease your ability to complete that movement, or increase pain during that movement. For example, in the case of an older adult with chronic knee degeneration, they often adopt a movement pattern of excessive right-to-left swaying as a strategy to offload their affected knee which requires more energy and makes it more difficult for that person to walk long distances. As another example, a young athlete may adopt a jumping pattern which both increases pain on the outside of their knee and limits the height of their jump. When considering that the ultimate purpose of your knees is to support your movement in a way that is efficient and comfortable, the ability to engage in movement patterns which promote efficient, effective, and comfortable movement becomes a critical aspect of long-term knee health

Tissue metabolism: Lastly, as we shift the loads through our joints by adopting different patterns or habits of movement, we can alter tissue metabolism. In Part 2, we talked about how different loading patterns can shift knee tissue metabolism to a state of chronic break-down and inflammation. Another way our movement patterns can alter tissue metabolism is by altering the flow of nutrients through the tissues, specifically the articular cartilage. The articular cartilage does not receive direct blood flow, so it requires frequent movement to gain nutrients and get rid of waste products. When this frequent movement is not achieved, either through changes in physical activity behaviors or limited motion of the knee during daily movements, the articular cartilage can fail to receive the necessary nutrients and begin to break-down.

Movement quality and knee degeneration

It is clear that the way in which we move our joints and the loads we place through them can alter how the tissues of our knee joint respond to our daily activities to ultimately promote long-term knee health or knee degeneration. With this mechanism in mind, scientists have been investigating the specific relationship between movement patterns and osteoarthritis development.

From these scientific investigations, it is clear that there is a strong association between osteoarthritis degeneration of the knee and progressive movement pattern deviations. In general, as a person develops worsening osteoarthritis degeneration, they begin to adopt movement patterns which decrease loading of the osteoarthritic knee. A person with osteoarthritis will demonstrate slower-and-slower walking speeds with shorter steps at a decreased cadence as the disease progresses. This is paired with a “stiffened-knee” movement pattern and a shift in weight-bearing and impact towards the unaffected knee. These changes in movement patterns have been shown to develop in those with knee osteoarthritis during many daily tasks such as walking, stair climbing, and getting up and down from a chair. As degenerative changes become more severe, we may see more drastic movement changes like limping, a rapid thrust or jerk of the knee to the outside with each step, and a side-to-side sway of the trunk or upper body. This means that movement patterns can be an accurate way of identifying and predicting a person’s stage of knee degeneration.

While these movement pattern changes are consistently found to be present in people with knee osteoarthritis degeneration, it is actually uncertain whether these changes cause greater degeneration. If a person is adopting a movement pattern to offload their degenerating knee, would it be beneficial, or detrimental, to return them to a “normal” movement pattern which increases loading on that knee? Do we have interventions that are effective for restoring “normal” movement patterns? If we did, would implementing them prevent or delay the progression of knee osteoarthritis degeneration? These are questions that scientists and clinicians have yet to answer.

While it is uncertain to what degree movement patterns directly contribute to the structural degeneration of the knee joint, it is important to remember that movement quality and function is often the whole purpose of maintaining knee health. Regardless of the impact of movement patterns on structural knee degeneration, the movement pattern deviations we see in those with progressive knee osteoarthritis, such as decreased walking speed, decreased movement efficiency, and decreased mobility, certainly have a negative effect on a person’s overall mobility and participation in daily life activities. Therefore, I believe that addressing these movement quality deviations early in an attempt to normalize movement and loading patterns is important to ensure long-term preservation of knee function and overall quality of life in the face of knee osteoarthritis degeneration.

How do we begin addressing deficits in movement quality?

We’ll certainly be talking more about addressing specific movement pattern deficits through exercise and movement retraining in future articles, but I do want to share with you now a general framework for how we think about movement pattern deficits in the context of intervention and treatment. When addressing these deficits, you or a healthcare provider will take the following steps:

- Identify the movement deficit and the desired movement pattern: This is all about understanding where you are and where you want to go. For example, you or a healthcare provider may identify that you are having difficulty and pain when putting your weight on your right knee during walking and stair climbing. This is leading to a stiff knee movement pattern, decreased walking speed, and difficulty with walking long distances or ascending stairs. Once this is identified, you or your healthcare provider can establish goals for how you would like to move like walking faster, placing equal weight through the right leg, and absorbing load through the right quadriceps during movement.

- Address underlying muscle function and structural limitations: Once we know where you are and where you want to go, we have to determine if you have the pre-requisite strength, mobility, and structural integrity to accomplish your desired movement pattern. In the example above, you or your healthcare provider may identify that your right quadriceps is significantly weaker than your left, or that your right knee doesn’t have sufficient range of motion to ascend stairs properly. In this case, you would need to address these strength and mobility deficits prior to doing anything else. Another possibility is that you have a permanent underlying condition, such as a congenital bone structure issue, a surgical fixation, or a torn muscle or ligament, which limits you from certain movement patterns. In these cases, you may need to find a work-around or compensation for your movement pattern.

- Movement retraining: Once we know how we want to move, and we have gained to pre-requisite strength and mobility to perform that movement, we can engage in movement retraining techniques. Movement retraining describes the structured learning process of integrating a new, and ideally improved, movement pattern into your daily life or routine activities. Movement retraining requires some form of feedback so that you can identify when you are moving incorrectly and make a change towards the correct movement pattern. This can be done by watching or paying attention to your own movements, but is it more effective when working with a trained professional or when using a feedback device.

By adopting this framework, you can begin to optimize your daily movement patterns to preserve your knee health for the long-run. If you are having specific knee pain or dysfunction, check out some of my other articles, or work with a physical therapist to determine whether movement patterns may be contributing to your issue.

Leave a comment